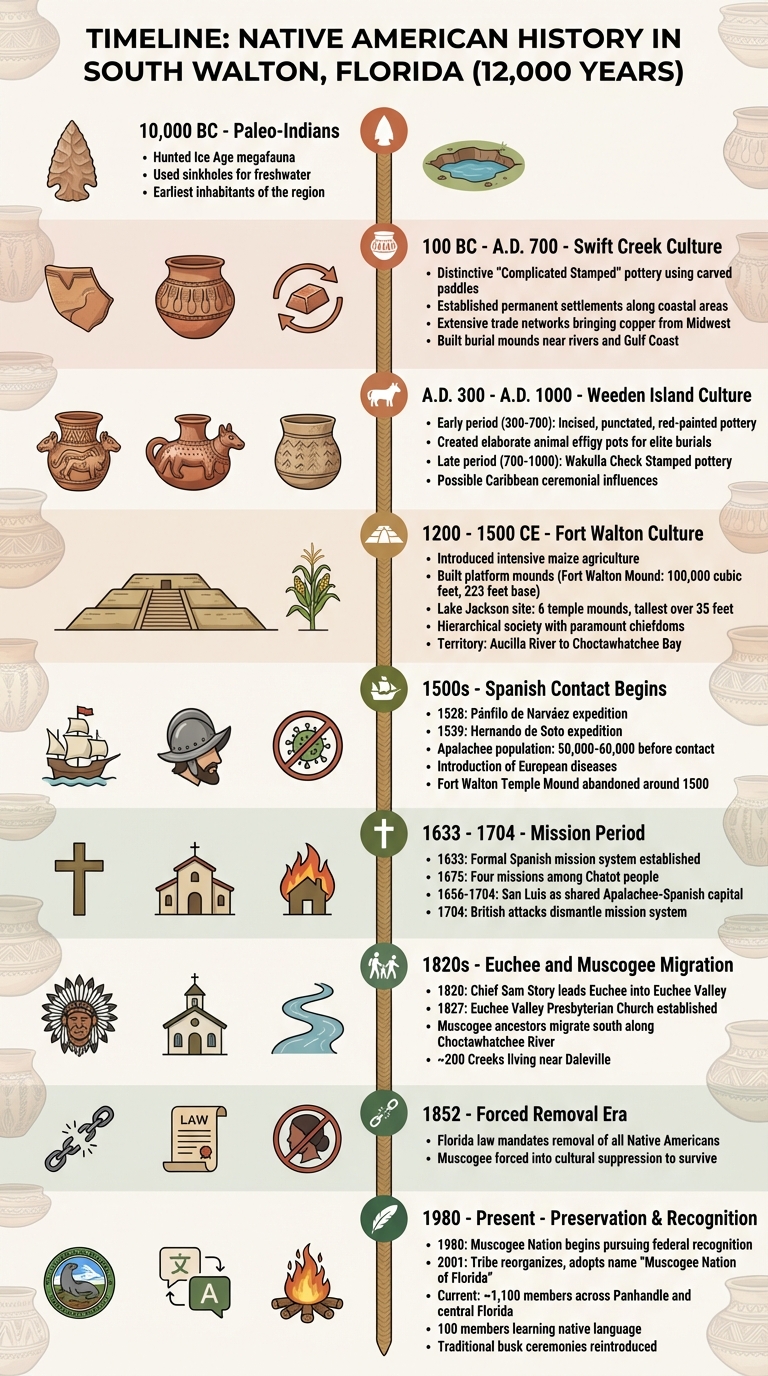

South Walton's history stretches back over 12,000 years, rooted in the presence of Native American groups like the Paleo-Indians, Chatot, and Yucci. These communities shaped the region through agriculture, trade, and ceremonial practices, leaving behind artifacts, mounds, and pottery that tell their story.

Key points:

- Paleo-Indians hunted Ice Age megafauna and used sinkholes for freshwater.

- The Fort Walton culture (1200–1500 CE) introduced maize farming and built platform mounds, such as the Fort Walton Mound.

- The Chatot and Yucci thrived along Choctawhatchee Bay, relying on fish, oysters, and crops like maize, beans, and squash.

- Spanish contact in the 16th century disrupted indigenous life, leading to mission systems and forced migrations.

- Today, efforts by the Muscogee Nation of Florida preserve Native languages, ceremonies, and history.

From ancient settlements to modern preservation, South Walton’s identity is deeply tied to its Native American roots. Sites like the Fort Walton Mound and Lake Jackson Mounds State Archaeological Site offer glimpses into this enduring legacy.

12,000 Years of Native American History in South Walton: Timeline from Paleo-Indians to Present

Early Inhabitants: The Chatot and Yucci Peoples

Chatot and Yucci Settlements

When Europeans first arrived in South Walton, they encountered two primary Native American groups: the Chatot and the Yucci. The Chatot lived in a region stretching from the Choctawhatchee River to the west bank of the Chipola River, with settlements strategically located around Choctawhatchee Bay. Meanwhile, the Yucci, who regarded themselves as the Southeast's original inhabitants, established villages along the lower Choctawhatchee River. This area, rich in natural resources like bays, bayous, tidal creeks, and freshwater swamps, offered an abundance of food and was known to the Yucci as "Am-Ixchel", meaning "Place of the Moon Goddess." The name "Choctawhatchee" likely emerged either from early settlers mistaking the Chatot for the Choctaw or through contact with Choctaw-speaking communities. These settlements formed the foundation of their cultural and daily practices.

Daily Life and Traditions

Both the Chatot and Yucci developed distinct ways of life that reflected their unique cultures. The Chatot spoke a dialect of Yama, also called Mobilian Trade Jargon, which served as a vital tool for trade and communication. The Yucci, on the other hand, spoke a language entirely different from the Muskogean languages of their neighbors.

The area's rich ecosystem supported dense Native American communities, as noted by Access Genealogy. These groups relied on the bay's resources, harvesting fish, oysters, crabs, and freshwater mussels. They hunted large game in the surrounding forests and crafted dugout canoes to navigate the mangrove-lined waterways. Their homes were round structures made from saplings, river cane, and thatch, while local clay was used to create pottery for storing food. To supplement their diets, they cultivated gardens with crops like maize, beans, and squash. By 1675, Spanish influence had reached the Chatot, leading to the establishment of four missions in what are now Bay and Jackson Counties. These practices not only sustained their communities but also laid the groundwork for future indigenous developments in the region.

Archaeological Cultures: Swift Creek to Weeden Island

Swift Creek Culture and Early Settlements

Long before the Chatot and Yucci tribes settled in South Walton, earlier indigenous groups left their mark on the region. The Swift Creek culture, which emerged around 100 BC and thrived until roughly A.D. 700, is particularly notable for its distinctive pottery. Their hallmark technique involved pressing carved wooden or clay paddles into unfired clay, creating intricate "Complicated Stamped" designs. These patterns were more than decorative - they reflected a society deeply connected to the broader Hopewellian traditions that spanned much of the Southeast.

Swift Creek communities established permanent settlements along coastal areas and waterways, forming extensive trade networks. These networks brought materials like copper tools and ornaments from as far away as the Midwest. Burial mounds near rivers and the Gulf Coast revealed crafted pottery alongside exotic items such as copper, mica, galena, and hematite. These finds indicate not only far-reaching trade but also the presence of complex religious rituals and social structures. This cultural foundation paved the way for the development of the Weeden Island practices that followed.

Weeden Island Culture and Caribbean Influences

The Weeden Island culture, which began to emerge around A.D. 300, built upon the traditions of the Swift Creek people while introducing new artistic and ceremonial practices. Interestingly, archaeological evidence shows that the two pottery styles - Swift Creek and early Weeden Island - were produced simultaneously by the same communities in Northwest Florida. As researcher Michael H. Lockman explained:

"The data suggest Swift Creek and early Weeden Island ceramics do not reflect separate cultural entities in this particular part of the Southeast during the Middle Woodland period. Rather, the data suggest that both ceramic series were being produced locally and contemporaneously by the same people".

| Period | Approximate Dates | Key Pottery Styles |

|---|---|---|

| Swift Creek (Middle Woodland) | 100 BC – A.D. 700 | Complicated Stamped (paddle-impressed) |

| Early Weeden Island | A.D. 300 – A.D. 700 | Incised, Punctated, Red-painted, Effigies |

| Late Weeden Island | A.D. 700 – A.D. 1000 | Wakulla Check Stamped |

Weeden Island pottery represented a significant artistic evolution. Instead of relying on paddle-stamped designs, artisans began using techniques such as incising (cutting into the clay), punctating (creating small impressions), and red painting. One of the most striking developments was the creation of elaborate animal effigy pots, often found in burial mounds. These pots, detailed depictions of birds and other animals, were typically associated with elite burials. As Karl T. Steinen from the University of West Georgia noted:

"Weeden Island burial mounds are best known for the inclusion of elaborate animal effigy pots in large deposits. These mounds represent the burial of a small number of elite members of the society".

Another intriguing addition to Weeden Island pottery was the appearance of hollow human figures, which were rare in Swift Creek ceramics. This shift suggests possible influences from Caribbean ceremonial traditions. By the Late Weeden Island period (A.D. 700–1000), the earlier "Complicated Stamped" designs had largely disappeared, replaced by the "Wakulla Check Stamped" pottery that became the dominant style in the archaeological record.

Destination Archaeology! Fort Walton Mound #archaeology #museums #nativeamerican

Fort Walton Culture and Agricultural Development

From 1200 to 1500 CE, communities in the region embraced intensive maize agriculture, a practice influenced by Mississippian cultures. This shift led to the rise of the hierarchical Fort Walton culture, which dominated the area for approximately 300 years.

Inland groups relied heavily on a combination of maize, beans, and squash to sustain permanent settlements. Meanwhile, coastal communities near Choctawhatchee and St. Joseph Bays focused on marine resources, showcasing different ways of thriving within the same cultural framework. Archaeological findings suggest that shellfish collection peaked during summer, aligning with the primary maize growing season.

These agricultural practices laid the groundwork for significant societal changes, including monumental construction and evolving religious traditions.

Platform Mounds and Religious Practices

One of the most striking features of Fort Walton society was the construction of platform mounds - large earthen structures made entirely by hand using sand, shell, and clay gathered from the surrounding area. The Fort Walton Mound, a prime example, contains about 100,000 cubic feet of material and spans 223 feet at its base.

These mounds weren't just architectural feats; they played a central role in the society's rituals. Leaders added new layers to the mounds in ceremonies symbolizing "world renewal", which reinforced social hierarchies. Researchers N.J. Wallis and V.D. Thompson noted:

"The repetitive act of covering the symbolically charged older surface with a new episode of construction is the key social dynamic of platform mounds. Groups or individuals that controlled this cycle of construction gained an important strategy for perpetuating social differentiation."

The flat tops of these mounds supported structures like temples, council houses, and chiefs' residences, built using wattle and daub - a method involving interwoven sticks plastered with mud. Access to the mounds was often limited to a single earthen ramp, typically extending toward a water source, while the mounds themselves overlooked central plazas surrounded by residential areas. Gail Meyer, Museum Manager at the City of Fort Walton Beach Heritage Park & Cultural Center, explained their importance:

"This mound was once the center of a city, perhaps the capital of a nation that stretched from the Apalachicola River to Pensacola. It was a ceremonial and political center, a meeting place, a rallying place for dances, games and public events."

Agriculture and Trade Networks

The ability to produce surplus maize allowed settlements to grow, ranging from small family homes to large ceremonial centers with multiple mounds. A notable example is the Lake Jackson site, which featured six temple mounds, the tallest rising over 35 feet. These organized settlements reflected the power of paramount chiefdoms that governed the region, stretching from the Aucilla River in the east to Choctawhatchee Bay in the west.

Trade networks also flourished, with major rivers playing a crucial role. Goods like greenstone, valued for crafting tools such as celts, traveled as far as 107 miles along the Apalachicola River and 50 miles up the Chattahoochee River. Around Choctawhatchee Bay, Fort Walton communities interacted with the neighboring Pensacola culture. The two groups were primarily distinguished by their pottery styles: Fort Walton pottery used sand, grit, or grog as tempering agents, while Pensacola pottery incorporated crushed shell in the Mississippian tradition.

sbb-itb-d06eda6

Later Tribes: Muscogee, Creek, and Euchee Presence

As the Fort Walton culture faded, new Native American groups began to inhabit the region. Among them, the Muscogee (Creek) and Euchee peoples became prominent in what is now South Walton.

The Euchee language stands out as a linguistic isolate, meaning it’s unrelated to the Muskogean languages spoken by neighboring tribes. Despite this, the Euchee often allied with the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, showcasing a unique dynamic within the region’s cultural landscape. These shifts in population and alliances laid the groundwork for the rich regional history tied to the Euchee and Muscogee peoples.

The Euchee Valley and Its Naming

Around 1820, Chief Sam Story led the Euchee people into the area that would later be known as Euchee Valley. Scotch travelers from North Carolina encountered Chief Story and visited his settlement. By 1827, this interaction between Native Americans and settlers led to the establishment of the Euchee Valley Presbyterian Church by fifteen charter members, marking an early example of cooperation between the two groups.

Meanwhile, Muscogee ancestors journeyed south along the Choctawhatchee River to escape federal removal policies. Records indicate around 200 Creeks were living near Daleville before this migration.

In 1852, Florida law escalated efforts to remove Native Americans from the state, forcing the Muscogee people into cultural suppression to survive. The Florida General Assembly declared:

"It shall be unlawful for any Indian or Indians to remain within the limits of this State, and any Indian or Indians that may remain... shall be captured and sent west of the Mississippi."

Such policies drastically disrupted indigenous life, setting the stage for future efforts to preserve and revive their cultural heritage.

Muscogee Nation of Florida Preservation Efforts

Despite these early struggles, the Muscogee community has shown remarkable resilience. Today, the Muscogee Nation of Florida is headquartered in Bruce, Walton County, and includes approximately 1,100 members spread across four townships in the Panhandle and one in central Florida. In 2001, the tribe reorganized its constitution and adopted a new name - changing from the "Florida Tribe of Eastern Creek Indians" to better reflect their historical identity.

Since 1980, the tribe has been pursuing federal recognition, a goal that Acting Chief Ann Tucker has described as vital:

"Federal recognition is everything to us. It's our sovereignty. It's our rights to protect our people."

The tribe has undertaken numerous initiatives to preserve and revive their culture. Around 100 members are actively learning their native language, while traditional busk ceremonies - once suppressed for over a century - are being reintroduced. Additionally, the Muscogee Nation of Florida operates a Muscogee Farm and runs rural relief programs, blending traditional practices with modern community support. These efforts represent a powerful recovery from the 19th-century policies that nearly erased their presence from the region.

Spanish Contact and Native Responses

Spanish Expeditions and Early Encounters

The arrival of Spanish explorers in the 16th century drastically altered life for Native American communities in South Walton. In 1528, Pánfilo de Narváez landed with a small group, followed by Hernando de Soto's larger expedition in 1539, which brought increased conflict. These expeditions left a trail of violence, including the abduction of leaders and forced labor imposed on native populations. The Apalachee people, whose population ranged from 50,000 to 60,000 before European contact, resisted fiercely. When de Soto's forces reached Anhaica, the regional center, in 1539, the Apalachee burned much of their town rather than surrender. During the harsh winter of 1539–1540, their warriors launched continual harassment campaigns against de Soto's encampment. These encounters pushed native leaders to adopt both defensive strategies and diplomatic measures.

However, not all interactions were purely combative. Christopher B. Rodning, a Professor of Anthropology, sheds light on the complexity of these relationships:

"During the sixteenth century, indigenous groups of the Native American South conceptualized Spanish expeditions as potential enemies but also as potential allies, and chiefs and chiefdoms pursued their own interests and agendas through diplomacy, warfare, exchange, acquisition of gifts and prestige goods, and other strategies and activities".

Some leaders integrated Spanish metal tools into their trade networks, using them as symbols of wealth. At the same time, diseases introduced by Europeans devastated native populations, weakening traditional leadership structures. This contributed to the abandonment of significant sites like the Fort Walton Temple Mound around 1500 CE.

Mission Period and Changes in Native Life

As Spanish contact deepened, native communities adapted to the evolving dynamics during the mission period. By 1633, the Spanish established a formal mission system in the region, including four missions among the Chatot people in 1675, likely located in what are now Walton and Jackson counties. This mission period, which lasted until 1704, brought profound changes to native life. Epidemics and external pressures led many Apalachee to convert to Catholicism. The settlement of San Luis became a shared capital for both the Apalachee and the Spanish colonial government from 1656 to 1704.

Despite these changes, Native communities displayed remarkable resilience. They built monumental council houses alongside Catholic churches and maintained cultural traditions, such as stickball games, even when these practices were discouraged by missionaries. As Christopher B. Rodning observed:

"The Apalachee council house at San Luis... was an architectural symbol of the vitality of the Apalachee chiefdom and a monument of sorts to the persistence of the Apalachee chiefdom within the geopolitical landscape".

Yet, the mission system eventually collapsed. Alliances with Spanish missions left tribes like the Chatot vulnerable to slave raids by British-allied Cherokee and Creek forces. By 1704, British attacks had dismantled the mission system, forcing surviving Native groups to flee their ancestral lands in South Walton and beyond. By 1717, the Spanish abandoned their policy of forced conversions, shifting to diplomacy with neighboring Muskogean groups. The displaced Chatot people eventually resettled in Mobile and later Texas, but they vanished from historical records. These events marked a turning point, forever altering the indigenous presence and legacy in South Walton.

Conclusion

South Walton’s Native American heritage runs deep, leaving behind a legacy visible in ancient agricultural practices and the impressive platform mounds that have defined the region for thousands of years. The Fort Walton culture (1200–1500 CE) introduced advanced maize farming techniques and established ceremonial centers that served as critical hubs for both governance and spiritual life. Even today, names like Choctawhatchee Bay - a sprawling 30-mile stretch - serve as living reminders of the indigenous roots woven into the area’s history.

For those eager to connect with this past, there are plenty of opportunities to explore. The Fort Walton Mound near Fort Walton Beach offers a glimpse into the ceremonial and political life of the region’s early inhabitants. Similarly, the Lake Jackson Mounds State Archaeological Site near Tallahassee stands as the largest known ceremonial center of the Fort Walton culture. Coastal ecosystems, preserved in places like Topsail Hill Preserve and Grayton Beach State Park, continue to protect the natural landscapes that sustained Native communities for generations.

Preservation efforts remain vital in keeping this history alive. Organizations like the Florida Museum of Natural History and initiatives such as the Aucilla River Prehistory Project work tirelessly to safeguard artifacts and archaeological sites from modern development. Meanwhile, the Muscogee Nation of Florida actively preserves Creek and Euchee traditions, ensuring that these stories remain part of the region’s cultural fabric. Whether through visiting these sites, supporting preservation projects, or participating in educational programs, there are countless ways to help protect and celebrate this heritage for future generations.

For a broader understanding of Florida’s indigenous history, the "Trail of Florida's Indian Heritage" offers a network of archaeological sites across the state, including many tied to the cultures discussed here. This self-guided experience sheds light on how Native peoples built intricate societies, navigated environmental shifts, and endured the profound challenges brought by European colonization. South Walton’s identity is far more than its modern-day appeal as a coastal retreat - acknowledging its indigenous roots enriches our understanding of the region, honoring Native American history as the cornerstone of its story.

FAQs

Why is the Fort Walton Mound important in Native American history?

The Fort Walton Mound, constructed around 800 AD by the Pensacola culture during the Mississippian period, was a focal point for ceremonial, political, and religious life. Thought to have been the capital of a regional chiefdom, this massive earthen mound ranks among the largest prehistoric structures along the Gulf Coast. Now recognized as a National Historic Landmark, it provides an important window into the deep cultural traditions of Native American societies in the area.

What impact did Spanish explorers have on Native American tribes in South Walton?

Spanish explorers first set foot in the South Walton area in the early 1500s, marking the region as part of Spanish Florida. Their arrival brought sweeping changes to the lives of the Native American tribes who called this land home. Along with soldiers, missionaries came with the goal of converting Indigenous peoples to Catholicism. They introduced European religious practices, material goods, and political systems, which began to reshape the social and cultural fabric of the local tribes.

Before this European influence, Indigenous groups in the area, such as those of the Fort Walton culture, had rich traditions. They were skilled mound builders, practiced maize farming, and created distinctive pottery that reflected their way of life. However, the arrival of the Spanish and their missionary efforts disrupted these traditions, leading to a decline in pre-contact practices and permanently altering the heritage of the region’s Native American communities.

How is Native American heritage being preserved in South Walton today?

Efforts to honor and preserve Native American heritage in South Walton revolve around archaeological research, education, and caring for the environment. Local historians and organizations work to shed light on the influence of the Muscogee (Creek) and Choctaw peoples, evident in place names, artifacts, and historical sites. Museums, such as the Indian Temple Museum, play a key role by displaying artifacts and sharing the stories that shaped the region’s Indigenous history.

State parks like Topsail Hill Preserve safeguard historic landscapes and cultural landmarks while emphasizing the importance of environmental conservation. Meanwhile, community initiatives and digital platforms, such as sowal.co, provide resources and guides to help visitors explore and appreciate these significant heritage sites responsibly. These combined efforts ensure that South Walton’s Indigenous history remains a meaningful part of its identity for generations to come.